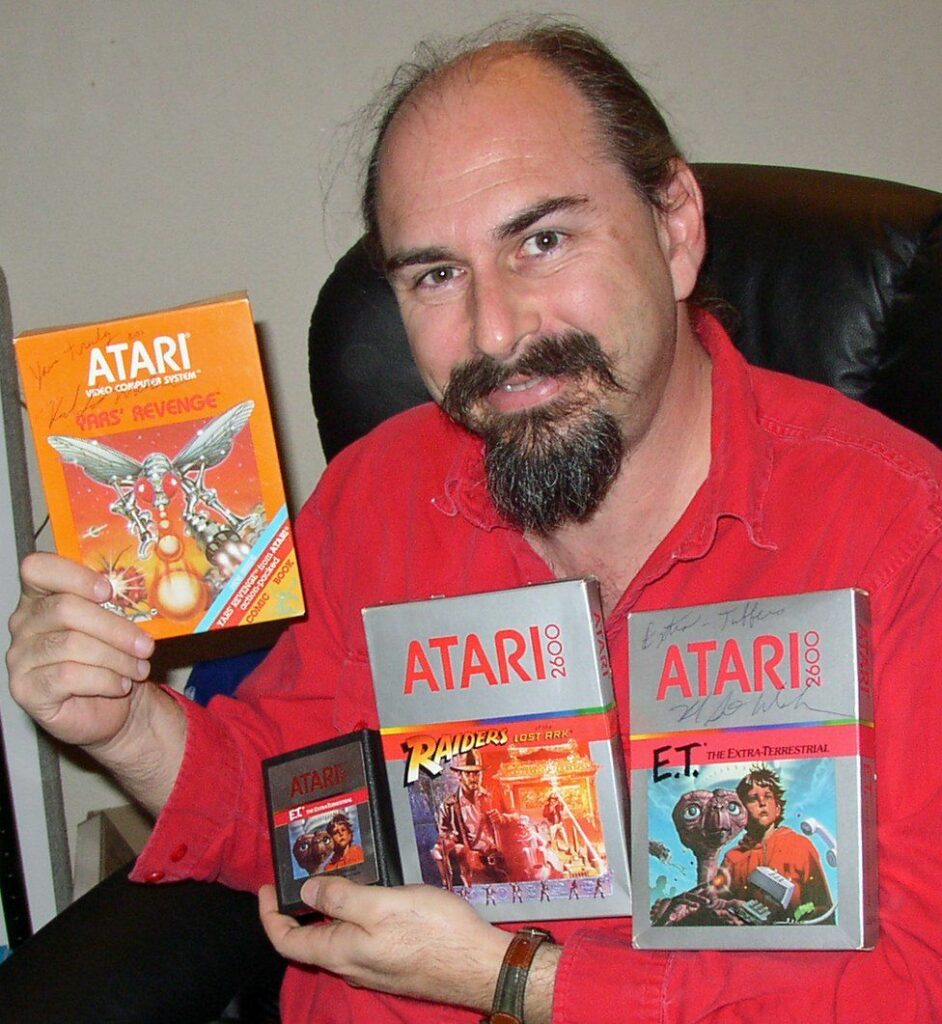

It was a fairly pleasant morning where we got to sit down with Howard Scott Warshaw for a video interview about his own place in the annals of video game history. Though I’d not been acquainted with him personally, his work quite literally preceded him- I’d watched YouTubers like The Spoony One cover E.T .for the Atari, and had heard as so many people had prior about the fabled E.T .Burial Ground- a landfill containing all the unsold copies of the Atari 2600 game, a result of the supposed death of the video game industry.

Meeting Howard, you wouldn’t think he was the man responsible for killing the video game industry- after all, years later, it’s alive and active as ever, and more importantly, he’d written a whole book about it- titled Once Upon Atari: How I Made History By Killing An Industry where he goes into detail about how that wasn’t his kill per se- but rather just a symptom of the times that lead to the first big crash.

“If you think about it its a pretty amazing thing that the license that caused the absolute most money of any license ever bought in video gaming history at that point was given the shortest schedule of any development by a factor of 5”, Howard says, having rushed the game out in 5 weeks, a record of game development if there ever was one.

Rather than be full of artifacts of its time, Howard’s story in the book about the development of E.T. would seem familiar to anyone remotely adjacent to the games industry- it’s a story of Atari spending large amounts for the E.T. license, political infighting and outfighting as former employees started up what would be the first third-party game developers and how the game industry crashed virtually over night.

“One of the pieces of feedback I get most is people who are in the industry saying the things that I talk about, the problems that happened at Atari and the weird inter-departmental frustrations and fights that go on are just as live today as they were back then”, Howard explains.

“That goes to one of the reasons I became a psychotherapist: Technology constantly changes, you have to update yourself every 5 years, it’s a lot of work”, he continues. “But people don’t change. Over time, people really don’t change”.

“The games that people ran into and the problems people had and the conflicts that people would run into back then, they’re the same conflicts that we have today. That’s the great part about being a therapist, I don’t have to relearn my trade every few years”, he continues. “The games are all the same, it’s just the tools and the toys that change over time”.

One of these examples would be the idea of developers breaking off from their parent companies to do something new- Howard briefly explained to us the story of Rob Fulop, who would leave Atari to start Imagic- another of the earliest third-party game developers.

“Imagic wouldn’t have happened necessarily except that after Rob did Missile Command for 2600 making tens of millions of dollars for the company, it came Christmas time and he was thinking “oh boy what’s the bonus gonna be. I’m looking forward to something because here it is I did a good job, I was a good boy, time to get paid off. What’s it gonna be?” “, Howard says. “He got his envelope at Christmas time and he thought, “Is it money? Is it keys to a car? What could it be?” he opened it up and it was a certificate to a free Turkey. That’s what he got”.

“My understanding is that he actually framed that and kept it in his office when he went to Imagic and he’s kept that in his office since”, he says.

Inventing Play

One thing that did change over the years was the idea of what play was. While now we have all our modern ideas like genres for games and ideas associated with them, it was a truly new frontier during the Atari days, with Howard and his colleagues having many stories of ways they had to engineer play- which is a fancy way of describing their productive goofing off sessions which would have been HR catastrophes if they took place today.

“It was a different time”, Howard says. “A lot of things that today people would not tolerate, the idea of things being intolerable wasn’t the same back then. That’s one part. Another thing is, one of the reasons there wasn’t this concept of intolerable back then is because people didn’t act up very much back then”.

“In general you didn’t see things like that, and you needed an environment where people could fully express themselves, just go nuts because your job was to break conventions, come up with brand new breakthrough ideas and make them happen and implement. It’s very interesting”, he continues.

“You need to come in to work, and at the end of the day you need to have created something that did not exist when you got up that morning. That’s a good day at work”.

He attributes a lot of the cultivation of this culture to Nolan Bushnell, founder of Atari:

“Nolan Bushnell did understand that well. He understood the idea that to have that kind of creativity going on, it’s not gonna make any sense in a corporate world.

So what he did was he created a facility where the engineering groups were really separated from the other groups. So the really outrageous things we were doing, and there’s a lot of accounts in the book of some of the really outrageous stuff that we did, we were insulated.

We were not just in a separate building, so we were insulated from the other corporate entities and other departments. Security had orders to keep the police away from us.

We were totally insulated so that anything that we did- and we could do anything we wanted to, as long as we kept games coming out. And we did. Pretty much anything we could and we did keep games coming out. And that was the deal.

It’s harder to pull that off these days. It’s harder to isolate a group and just have a free for all area in a company these days. You’re absolutely right, what we did back then would be a total HR nightmare today”.

The Many Steps To Yar’s Revenge

One thing Howard stressed was the one-on-one nature of Game Development back when he started out. Howard is a man of many majors- Computer Science, Math, Theatre and Economics, when he started out- and he brought it with him into his first project, the critically-acclaimed Yar’s Revenge:

“If you think about it, it’s true that a video game is a computer program and it’s a technological product, but the reality is its an entertainment product”, he says. “And if you’re gonna make an entertainment product, first of all you need to have a sense of entertainment, you need to produce joy, not just a functioning technical spec”, he explains.

“With economics, people think about it as the study of money but its not, really. Economics is the study of allocation of scarce resources. And there was never a more scarce resource, I think, than the 2600 and trying to program that machine with just 128 bytes of RAM and about 4k of memory. That was all we had to work on that machine to do all the games that we did, it was pretty remarkable”, he adds. “So economics help me manage a really scarce resource and theatre helped me really put some pizazz in the games and really make something exciting and visually compelling and stimulating”.

It should be pointed out that while the Atari games of the 2600 might have been associated with drab backgrounds or worse, the visual complexity of Pong, Yar’s Revenge was anything but- the game was a shooter full visual flair, enough to give games like the Touhou series a run for their money.

This was all despite that compared to what was in the arcades, the 2600 was severely lacking in power. While Yar’s Revenge started as a 2600 home port of an arcade game, Howard explains that he wanted his industry debut to be so much more than that.

“The original assignment of Yar’s Revenge was to convert a coin op game, Starcastle, to the 2600. When I looked at what they had done with the specialized hardware for Starcastle and I looked at the 2600, even though I hadn’t been there long I realized this was gonna suck”, he says. “This game was gonna suck, and I could not afford to have my first game suck”.

“I managed to talk them into letting me go into a different direction, redesign the game mechanics to something that accommodated the 2600 more comfortably and that’s the game that went on to become [a success]”, he says.

While the story of Yar’s Revenge ended up being an extension of the story of how Howard got to Atari, he says you wouldn’t see similar stories in the industry simply because game development has moved on from the idea of one-man shows (At least in triple-A development).

“It’s an interesting idea, because back then it was a work of authorship. There was one person who was doing the entire game. At that point, being an interdisciplinary individual was a huge benefit. Really meant a lot”, he says.

“Nowadays at least for console gaming people are a lot more specialized. You don’t impact that many areas of the game in a lot of cases. So that kind of breadth in background isn’t necessarily as big a contributor to your ability to making a modern console game. Now the depth in the one area you’re responsible for is more important than the breadth to cover multiple areas”, he explains.

“Back then, it was essential and I was really glad to have that. And it was essential. To me it was kind of a shame, and that’s how its gotten to. Because I love the idea of being able to touch all the parts of the game and being able to put them and combine them in ways that exploit each other in positive ways that achieve a synergy that’s harder to do these days because everything is so segmented and specialized”, he adds.

Developing Games On A Cruiseliner Vs A Motorboat

That being said, it’s not like Howard is exactly saying we need to return to those days. From his tone, you could tell he was someone who’d accepted that this was simply how the past was, rather than an ideal we should strive back to. That being said, the torch of coming up with something new was passed to a newer section of the games industry- the indies.

“There’s two aspects right, there’s Console gaming which has gotten so huge and enormous, and no one can really just do that on their own. Fortunately the industry has also developed this second branch off, the indie game”, he explains. “Now there are app-based games and we’re back in a world where one person really can create a new and experimental game. I’m totally in favor of that”.

He went on to talk about how it’s not a case of one branch being better than the other, but rather a fact that the scale of each type of game lends it different strengths:

“The way I compare them is: I see console gaming now as an Oceanliner. A luxury liner. Whereas the [Atari] 2600 was like a motorboat”, Howard explains. “The thing is a luxury liner can hold a lot more people, a lot more equipment, a lot more stuff, a lot of great things and you can have a lot of great time on a luxury liner. But the one thing you can’t do on a luxury liner is change direction very easily”.

“The great thing about independent and small-scale game development is that when you get that concept, you get that magic moment you realize “oh wait the game should go over here not over there” you can do it. And you can totally redirect and redesign your game and come up with something innovative and special”, he elaborates. “In a console game you just cant do that anymore because its too big a commitment”.

While you could hypothetically radically shift triple-A development, such cases are more often the exception, instead of the rule.

“I like the idea of shaking things up and creating something new”, Howard says. “The problem you have is that really big developments command really really big budgets. Really big budgets present really big risks, and nobody likes really big risk when it comes to money. Well, some gamblers do but investors don’t, that’s for sure”.

“You have to be careful and that’s what makes the cruiseship model so tough. When you have that kind of investment and that kind of aversion to risk, your options are reduced”, he elaborates.

“If you’re on a large team, team-building and consensus building is just as effective for changing the course of things as it is for maintaining the course or path of things”

So does that mean every triple-A game is fated to go from concept to launch without any spark of creativity? Not so much. As Howard explains, it just takes leadership to do so:

“What you have to learn at that point is that even though you don’t have the speedboat, you don’t have the freedom to just go in a different design direction if you want, you have to remember that on a large ship you can’t just grab the rudder and turn it- but what you can do is convince the entire crew that maybe we’re going in the wrong direction and maybe we should start updating our maps and start thinking about going somewhere else”, he says.

“Instead of it being a purely design challenge or purely a technical challenge to implement something different, it becomes a political challenge”, he elaborates, referring to politics as the dreaded P-word. “Fact is if you’re on a large team, team-building and consensus building is just as effective for changing the course of things as it is for maintaining the course or path of things”.

“If you really wanna make a difference and shake things up as it were, you need to start a grassroots movement instead of just yelling and screaming. Because one person yelling and screaming at a large group doesn’t really make much noise”, he notes. “But when you get half of a group saying “we need to really be going over here instead of over there” it’s hard to ignore that. Ironically, people accuse videogames of creating more isolation and separating people and isolating people because they’d rather play than engage with other people”.

“Video game development has become a highly human interactive experience. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, it doesn’t have to be. You can use actual people skills and that’s how you’re gonna shake up modern development”, he says.

Hot Button Industry Topics With Howard Scott Warshaw

Having a legend of the games industry on the line with us, it would have been remiss to not pick his brain about some of the big issues in the game industry right now. One of these that was particularly relevant was the idea of unions- as someone who had to build a game from zero to finished in five weeks, he’s sure to have some thoughts on the industry’s first step towards unionization.

Howard was largely in favor of unions- after all, as game development gets bigger and bigger in scale, there would need to be tools in place to make sure the artists at work are working in good conditions.

“When the people who work for you are just broken and drawn out to their limit, when you try to use people up, you also use up their output”, Howard explains. “If you drive people too far, too fast, too hard, you end up breaking the machine and everything falls apart, you don’t get what you need in the first place”.

According to Howard, unions are pretty much proof that bad working conditions aren’t a debatable point- instead, they wouldn’t be discussed if things weren’t so bad that they were needed.

“The idea of Unions only comes about when there’s a cohesive labor force that recognizes the fact that something’s going too far. If you look at it historically, there’s a really key point that sometimes gets overlooked in the discussion of unions. Video game shops now are equated to sweatshops. They really are pretty brutal, people demand ridiculous, incredible hours all the time, people have to be there on the job almost all the time, they have to sacrifice the rest of their lives”, he says.

He goes on to explain that that’s very much the case with his own experiences, where some companies would even have clauses that say they could cancel your paid time off if they felt the studio was currently in crunch. The idea is simple: Even your contractually obligated perks were optional if it endangered the release of the product.

Of course, that’s not to say that all overtime is bad. According to Howard, what changed between the Atari years and now was simply who was telling you do do the overtime:

“At Atari, you also found people there all the time. You found people there day and night, there was always someone there in development at Atari, they were just always there”, he says. “The difference is nowadays people are commanded to be there. They are required to be there, sort of the office space thing. “I think maybe you oughta come in this weekend”. I had to play that manager for a while at some places that I worked”.

“That’s when you get the kind of unhappiness that can result in a union out of the need for protection. It never came up when people really needed to be there in the first place”

” At Atari, people were always there, no one ever asked them to. At Atari, people were there because they wanted to be there all the time. Because what they were doing was so compelling and so important to them that they needed to be there all the time. So the tradition of being at work all the time trying to hit the schedule and trying to make something come together and happen kinda started at Atari”, Howard explains. “But at Atari, it happened because that’s where we wanted to be. That’s really what we needed to do”.

“It has evolved into the demand of it, and part of that is because at Atari it was one person, one game”, he explains. “The sense of ownership , the sense of responsibility was huge. When you’re on a big team, it’s cool to be on a big team but the buy-in is not the same. It’s not the same having the whole game be your responsibility versus you being one cog in a huge machine that’s making the game”.

“You don’t have the same sense of buy-in, you don’t have the same sense of responsibility and that means when somebody has to make you be there, 24 hours a day or all around the clock, that’s not the same as you having the mad desire or the need to be there. There was never a talk of unions at Atari. There was just “Get them out of our way, and get us a little more schedule room so we can make the game as good as we possibly can” because that’s what we needed to do”.

Howard seems to draw the causal line as more of something related to the scale of game development now- with the more pipeline based approach of game development, late nights are more likely to be the result of a higher up trying to hit their deadlines than the lone animator or programmer doing so.

“One of the reasons I think you do have unions today is because you don’t have the same of individual buy-in in the project, you don’t have the same kind of power or responsibility over the project”, he stresses. “And you do have people who are responsible demanding that all these other people have to comply to their rules, have to come along and be there when they don’t necessarily want to. That’s when you get the kind of unhappiness that can result in a union out of the need for protection. It never came up when people really needed to be there in the first place”.

In contrast, he reiterated that smaller development teams are operating on passion instead:

“I bet there are app development teams and small groups working on truly innovative new projects that are there all the time, that are putting in every spare minute they could. Those people have really lit the fire. They know the passion of trying to move your hot concept forward, as opposed of just trying to squeeze a few more polys into the same game”.

No Excuse For Sexual Harassment

Another issue we just had to ask Howard about was the ongoing cases of sexual harassment in the games industry. In his book, he does describe a very ideal type of game developer, the mythical creative with no sense of boundaries. While it’s a great mythos in hindsight recent years has seen that persona used to cover up all sorts of ghastly behavior- which Howard didn’t take too kindly to.

“As a therapist I’m keenly aware of these sorts of issues and things like that. It was different”, Howard says. “But I always say that real innovators are people with boundary issues. Because it’s their job to break convention, its their idea to not be bound by convention and by typical thinking. They need to break past that”.

“There is a difference however, between being someone who does not respect boundaries and someone who does not respect other people”, he says, denying the excuse that being a creative goes hand in hand with being a sex pest. “It’s my feeling that you can attack conventions and boundaries and still respect other people. That’s an important differentiation”.

“If you don’t respect people, that’s not the same as free thinking. That’s just disrespect”

He goes on to elaborate that at Atari, although he talks about things like walking around with a bullwhip or throwing fruit around, there was still a central respect between the hardworking people making games. Rules, however, were a different story:

“You need to respect people, not necessarily social conventions, thinking conventions. The main kind of boundaries we were trying to break through were thought boundaries. Not really behavioral boundaries. Although some of those did get trampled occasionally… There’s no doubt about it”, he says.

“There are people who use that excuse to say “well I’m just a free thinker, I’m just going. You can’t hold me responsible” “, he says.

“Just because you’re capable of thinking outside the box doesn’t mean you can pretend boxes don’t exist. If you don’t respect people, that’s not the same as free thinking. That’s just disrespect. I really don’t think that’s appropriate, you don’t have to disrespect people to be creative, in my opinion”.

He also stressed another aspect, which was not forcing your way of life on people. In the book, he tells the story about how Atari had a strong group of people who smoked weed. That being said, partaking in the activity was never mandatory, either. In a sense, that kind of acceptance is the boundary-breaking he was looking for.

“It’s funny how sometimes it is true that people one way- if you’re not gonna respect boundaries, you should respect all kinds of aspects. There’s all kinds of ways of not respecting them”, he says.

“There’s people who want to challenge things and people who don’t. They’re all commitments to a persons individual goals and commitments and ideology, right?”, he elaborates. “If I tell you you must break this boundary with me to be ok, how is that different from someone who says “You can’t break that boundary to be okay?” “.

“Controlling other people isn’t where it’s at, it’s about not being controlled by others in a way that’s inoffensive. It’s a tricky balance to walk. But I think what keeps coming back to my head is that there’s a difference between playing with boundaries and respecting people. You can’t lose the respect for people or it all breaks down”.

Keeping Games Alive

We also shifted gears to talk a bit about a less dramatic but equally important part of the games industry, preservation. The setup is simple- you can’t buy an Atari 2600 anymore. But for many, playing a game like Yar’s Revenge or Missile Command is a big part of gaming history. To that end, many interest groups are working to make sure there’s some sort of way to enjoy these games, be it by physically preserving copies of them and the hardware they were made on, or having digital backups playable via emulation.

Howard shared his thoughts on that with us, too:

“I like it. I’m very much in favor of that because whether it’s therapy or video games or anything else, the past is the past, and we can never change the past. But the past is a very important indicator and informant of our present and our future. If we’re really gonna understand where we’re going, sometimes we have to understand some aspects of where we’ve been and where we came from”, he says.

“The idea that as we get to the point where the hardware is harder and harder to come by, people have found other ways of playing the games and emulating the games, and running the games so that you no longer need the actual hardware, and you can still have the original gaming experience”.

That being said, he also proposed a new element of the preservation angle: the history of it as well. While years from now E.T. may just be another file in the archive, the context of why it’s such a big deal is a whole separate entity. That kind of context is important for the history of games, just as it would be for any other medium.

“There’s people like me who are still around to tell some of the stories and preserve some of the lore that went on back then. Because I think it’s important for people to understand where we came from, and to know where we’re going”, Howard says.

“That’s one of the major things about Once Upon Atari is that it documents a tremendous amount of the original lore and places a lot of what went on and the stories that people hear about or the myths that people hear about what went on back then, it places it in the proper context”, he continues..

“So people can understand what it means to have been there, what it was like to go through that, and how a lot of the machinations that went on in Atari, in terms of the business and in terms of the inter-departmental conflict, in terms of the infighting, in terms of the things that determine the environment, in terms of the cultural shift that lead to the downfall of the industry for a little while”, he goes on. “A lot of the same things are still in operation today, they’re still happening today. So those who do not learn the lessons of Once Upon Atari are doomed to repeat them”.

So, Let’s Talk About E.T.

For better or worse, E.T. will be a game that follows Howard Scott Warshaw for the rest of his life, as it will Atari. The game’s a veritable part of the games industry’s history, floating ominously over the company with its neck outstretched, in one hand; a radio part and another; a Reese’s Piece.

Funnily enough, while E.T. earned a moniker of being the worst game of all time, Howard says he doesn’t really quite mind the association.

“I was fine with that. E.T., it’s not the best game, I don’t really think it’s the worst game, but I like it when people call it the worst game. I actually prefer that”, he says.

Howard shared with us his thoughts when the time finally came and they’d unearthed the buried pile of E.T. in the landfill:

“For one thing there was a really beautiful aspect to it in that every game I ever did, I wanted it to be groundbreaking. It was really ironic to me, because when they pulled up to me even E.T. had become groundbreaking. They had to break the ground to find it”, Howard says.

While some people act as if Howard had created E.T. to spite the human race, Howard says his memories of the game are largely positive. If nothing else, the fact that his 5-week project would command enough pull to bring people out to the middle of the desert decades later was proof that he had created an emotionally engaging piece.

“In that moment I realized that this little 8k of computer code that I had written over 3 decades before, was generating excitement and interest and joy on the part of so many people, and I thought that something that I did all that time ago is still creating some real solid and positive human experience, it was overwhelming to me”, Howard explains.

“People thought I cried because I was so sad to see the game was actually there. But no, I was overwhelmed with joy in that something I had done was able to bring that much happiness to so many people in that moment and so much excitement. There’s nothing I’d rather do”, he explains. “I felt so overwhelmed with the emotion of the moment that I literally couldn’t talk, which doesn’t happen to me very often”.

While it lacked critical praise, part of Howard’s attachment to E.T. was the act of bringing it into existence at all- just its development story was enough to warrant it a spot in the annals of history, after all.

“It felt really good to be there in that crowd. E.T. was a landmark development and it honestly never felt like a failure to me. I had achieved it- I had a solid game that I completed in 5 weeks that passed QA and went out. It was released. And even after all the returns it was still a million-seller”, Howard says.

“I think I’m still the only person who released more than one game who can make the claim that every game I released for Atari was a million seller. Every single one”, he continues. “E.T. was no exception, I’ve always been kinda proud of that. I’ve learned to have a sense of humor about it because I believe a sense of humor is an essential survival trait in the world today, especially today”.

“It was a deep, resonant feeling of satisfaction to think that I produced something that after all this time, after all these years later, was still generating excitement, interest and focus. It was a deep, deep honor and it was an amazing moment of my life”, he adds.

The Hypothetical Complete E.T.

While getting E.T. out at all in the situation was to be commended, it’s not like Howard hadn’t thought about what he’d do differently. Given different increases to his schedule, he reflected on how he’d do things differently:

“The one thing E.T. does that’s really a problem, of all the problems in E.T., the one fundamental problem is that E.T. commits the cardinal sin of videogaming: In videogaming it is OK to frustrate a player. In fact, I believe its necessary to frustrate a player so that winning has some sense of satisfaction. But you can never disorient the player, that’s the sin. You should never disorient the player”, he says. “And in E.T. there were too many places, especially when you’re first waking up to the game, where the player can become honestly disoriented where you suddenly don’t know what’s going on”.

“There’s a big difference between frustration and disorientation. Frustration, I can see the cookie jar but I just can’t reach it, I can’t figure out how to get it”, he goes on. “Disorientation, I step into the kitchen to get the cookie and I find myself in the garage for some reason. There’s too many moments where if you understood the game you’d know what happened, but whne you first start you don’t. And it just feels like suddenly I’m over here, I’m over there, I don’t know what I’m doing and I’m stuck. And that’s no good. So I would have done something to address that”.

Dealing With The Schedule

Howard explained that the schedule really was the biggest obstacle when it came to making E.T. While a long development cycle may not necessarily yield the best game, a short dev cycle definitely contributes to a bad one.

“If I would have had an extra 4 weeks or more, a month or to, then I would have redesigned the game”, he laughs.

“The thing about E.T., ordinarily when we make a game the game would take 6-8 months because what you’re doing is you’re trying to make a good game. And you’re gonna see how long that takes. The variable is time, it’s not quality”, he says.

“When you only have 5 weeks, it’s a design problem. It’s not a programming problem. It becomes a design problem, and the problem is “what’s a game I can do in 5 weeks and how do I make it good”.

He explained the process of making the game:

“Ordinarily you say “well its gonna be good and I’m gonna see how long it takes”. When time is the limited variable, the independent variable is quality. So what I did was I have a fixed schedule, so I need to do a game that can be done in 5 weeks, so that’s what I did. I designed a game that I could complete in 5 weeks and then I did everything I could to figure out how I could make that the most fun game it could be”.

“So that’s an inversion in design thinking. How it worked out? Well, there’s a whole lot of history about how it went. Would it have changed history? Absolutely it would have changed history. Because if I take some of the real fundamental problems out of E.T., in just an extra couple of days, then instead of being the worst game ever made, which is how its frequently identified, it would have been an OK game that went out, sold a few million, and away we go”.

Had E.T. not been weighed down by its limited development cycle, Howard’s adamant its place in history might have changed for the better.

“It wouldn’t have been a controversy, it wouldn’t have been an uproar. The video game crash still would have occurred, they would have had to blame something else for it. So it would have changed history that way”.

The Rise Of The Atari-Style Game

One thing that’s risen alonside indie games is the throwback visual. People love making games look like they were made on older consoles, with titles like the NES-like Shovel Knight.

I managed to show Howard one such game that had Atari as its major influence- indie horror game Faith, which spurred quite a bit of discussion about the circular nature of game development.

“So many things go full circle. In some ways the gaming industry has gone full circle, in that it used to be one person, one game, small console development. Consoles grew and grew to become humongous gargantuan operations”, Howard says. “At the same time, handheld development emerged and it emerged back with the idea of one-screeners and simple gameplay and apps and development games that would be very small and could do new innovative things and try new things. In a sense the game industry grew beyond that capability and then circled back to being able to provide it once again”.

“And I’ve gone full circle. I used to make video games to entertain nerds, now I’m a therapist who’s actually trying to make their lives better in a very real and fundamental way. What I just saw in that clip is another kind of way that we circle back. Because what I’m seeing there is a fusion of- what we just saw, you could never do that on a 2600. I don’t think that’s really doable on a 2600”, he notes.

“But it has the look and feel of a 2600. So what they’re doing is they’re taking the look and feel of a classic game and co-opting it into a production that’s much more sophisticated than anything you could have done then. But it still has that feel, so it’s like a nod to the classics, but it still really lives in the present. And I think that’s really exciting. That’s kinda cool, the idea that you can use the origins of something to refuel it. And to spin it in a way that adds depth and dimension to it and still use very modern technology to execute. Was that done on a 2600? I’d be pretty impressed”, he says.

Of course, it’s not just small indie developers looking to make an Atari-inspired game. Before we ended the interview, Howard dropped one last bombshell on us: that Yar’s Revenge would be coming back.

“I have signed a deal with Atari to do a Yar’s Revenge sequel. There are other Yar’s Revenge products coming out from Atari, but I am actually going to design and oversee a development for an actual HSW Yar’s Revenge sequel. It’s a design I’ve had in my head for decades, I’ve thought of doing it , I’ve wanted to do it”, he says.

“It’ll be on a number of platforms, It’s not initally going to be a 2600 game but it’s going to be a game that could be developed on the 2600 because it was designed on the 2600.”, he explains. “It’s a gameplay I’ve had in my head for many years, all these decades, I’ve never seen this gameplay done anywhere else. I think it’s a really exciting- people think what makes Yar’s Revenge well it’s Yar, its the glittering Ion Zone, that’s what makes Yar’s Revenge”.

“That’s not really the way I see it. To me what makes a Yar’s Revenge game is super high stimulus and audio visual overload. Something that’s really a symphony and a bounty for the senses. Something that grabs your attention and will not let it go and keeps the player super engaged on multiple levels all the time”, he continues. “And I think this game is going to do this far more than Yar’s Revenge did. I’m pretty excited for this opportunity, I think this is gonna be very cool”.

“I don’t have a release date for it, it’s gonna be a little while. But I got the design together, we’re gonna be moving forward and its gonna be pretty cool”, he says.

Unlike the original which had a fully-staffed team of one team, Howard says this sequel to Yar’s Revenge will be sporting a more modern-sized team- under his supervision, of course.

“It’s gonna have the original one person lead design team which is me, but I think this is gonna be a development that’s gonna be designed by a team. Fortunately I do have some development- I went back to 3DO, and some other experience. I do have experiences leading teams, in larger developments also”, he says. “But I’m mostly gonna be the design consultant and the design originator on this game. We’re pretty excited about it”.

From throwing fruit to making a piece of the games industry to even acting as a therapist for disappointed children who played E.T, there’s no doubt Howard Scott Warshaw has lead an interesting life. With Atari approaching the 50th anniversary of the 2600, it’s been nothing short of a delight to hang out with one of the pioneers of that era- even moreso talking about all the happenings of way back then.

Our thanks to Howard for sitting down with us and talking shop, and you can read more about the Atari days in Once Upon Atari: How I Made History By Killing An Industry.

![[ASIA EXCLUSIVE] Bringing Back a Classic: Inside the Making of FINAL FANTASY TACTICS – The Ivalice Chronicles](https://cdn.gamerbraves.com/2025/06/FFT-Ivalice-Chronicles_Interview_FI2-360x180.jpg)

![[EXCLUSIVE] Gearbox Executives Share Details on Borderlands 4 – Story, Weapons, and Lessons Learned](https://cdn.gamerbraves.com/2025/06/Borderlands-4_Interview_FI-360x180.jpg)

![[EXCLUSIVE] Wan Hazmer Reveals How No Straight Roads 2 Expands Beyond Vinyl City with Shueisha Games](https://cdn.gamerbraves.com/2025/06/NSR2_Interview_FI-360x180.jpg)